Small Worlds and Large Worlds

This essay is the second in a two-part series exploring institution design in the polycrisis, focusing on the contexts in which agents operate—known as large worlds and small worlds. It examines the characteristics of these worlds, the ability to make predictions, and the relationship between agents and worlds. Read Part 1 at Agents and Institutions.

This essay is based on transcripts of a series of original audio recordings of our conversations with Jon with minor edits for clarity and length.

In our exploration of agents, we must also consider the contexts in which they operate. I find it useful to think of these contexts as large worlds and small worlds.

What Makes a World Small or Large?

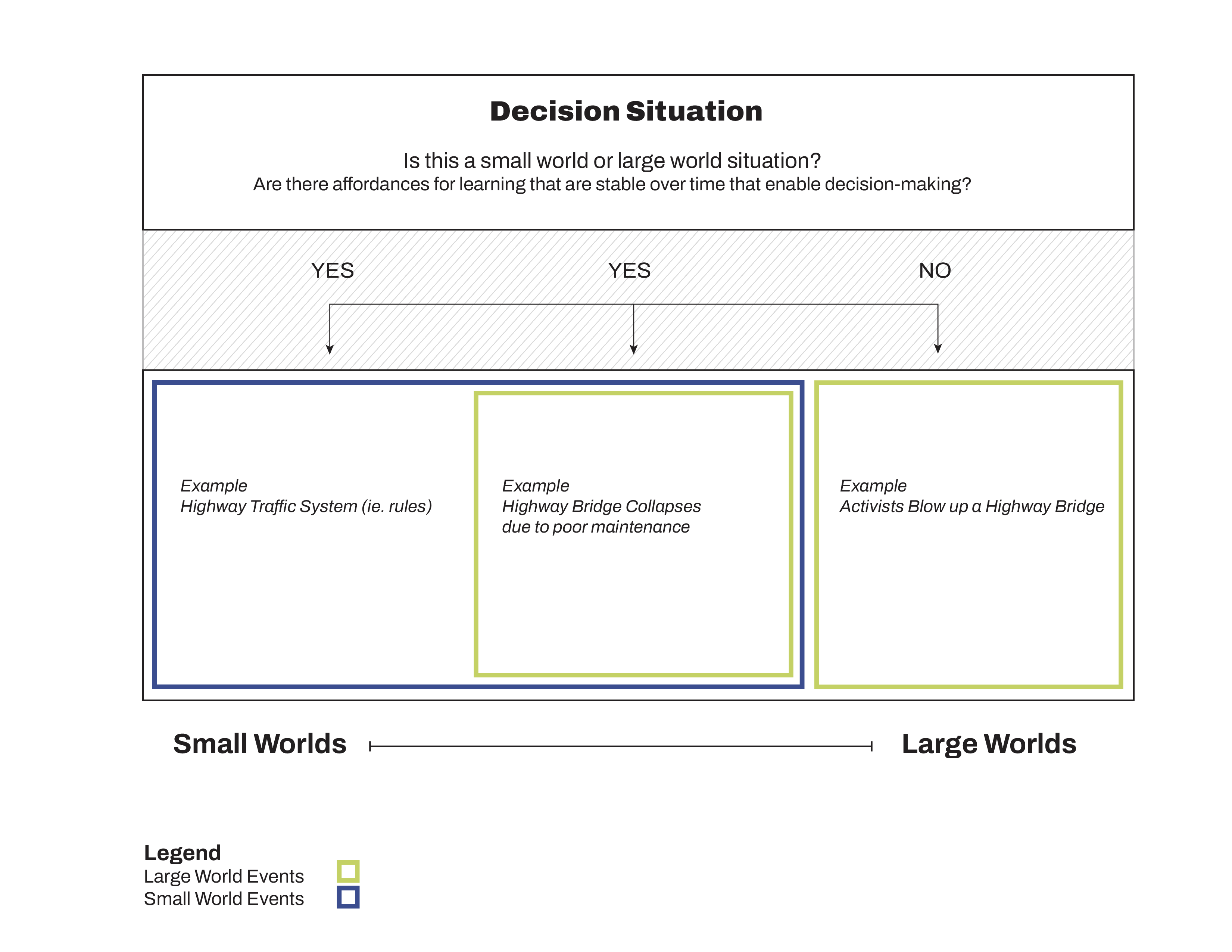

The distinction between large worlds and small worlds is disarmingly simple, it's a concept that's easy to intuitively explain but difficult to make precise. Small worlds are environments where we can make predictions, where regularities are created by institutional contexts. This isn't about geographic smallness; it's a property of an institution, a built context, or a system. Large worlds, on the other hand, are characterized by unpredictability, complexity, the absence of clear patterns, and the lack of affordances for learning.

To illustrate in a kitschy sort of way, the highway and road system could be considered a small world since it has a high degree of predictability. Most days, we decide to drive some place and we get there. There are regularities created by institutional contexts, traffic rules, and informal norms. Even when people break these rules, they do so within a more or less predictable range. There are wild cards, like being wary of things that might fall out of the truck in front of you or watching for children in a residential neighborhood. We slot these wildcards into a category of “predictable unpredictables.” Within these constraints, we can make predictions with a high degree of reliability. The rules are clear, and the variables are known—including the “known unknowns.”

In the same vein, agents (such as doctors) working inside a clinic operate within a small world characterized by a finite set of possibilities that I break down into four categories: Filter, Infrastructure, Action, Diagnosis (This set can be formalized mathematically in terms of Bayesian game theory). A patient is in front of a receptionist who filters where the patient should go, a doctor requests a test (action), leading to a diagnosis (a stereotyped categorization of the situation at hand), leading to treatment—more actions. However, this action in a small world isn't isolated; it presupposes an infrastructure. Specifically, it needs the clinic, the availability of drugs, the training of the doctor, biomedical research, and so on. So, an action in a small world needs all four components if it is going to be predictable (in the sense that we can assign it a probability that can then be verified through future observations). It needs a filter to reduce the possibilities to a finite range. It needs some kind of diagnostic mechanism to categorize the state of the world one is acting in. ****It requires a set of actions to choose from that produce a predictable results within this state of the world based on a model, and finally, it requires an infrastructure supporting that action.

But then there are large worlds where the ability to make predictions in the above sense diminishes or disappears. In large worlds, you encounter what I refer to as large world events. Consider the same highway system. What if a bridge collapses due to the lack of maintenance over the course of decades? That's a large world event within the context of a small world. It's unpredictable and it changes everything. However, the infrastructure supporting the traffic system is also small world. In this case, we are speaking of largeness relative to the model of the driver, not largeness in an absolute sense. Even so, if you're working from inside the small world of traffic, there are not resources within that model to think about maintenance being done on a bridge. So “maintenance being done on that bridge” is outside of your small world. If that bridge collapses because of an absence of maintenance over the course of decades, relative to your small world, that will be a large world event. But there is another system in place that says, “all right, if we don't do maintenance on this bridge, we can predict that it will collapse in this period of time because of engineering principles”. So, the collapse of the bridge in and of itself is a large world event in a relative sense, but not in an absolute sense – there's another small world within which it's predictable.

That being said, there is no “largest world,” sort of like there is no one largest set in set theory. There is no “one world to rule them all, one world to bind them.” One promise of modernity—including its revamped versions such a predictive analytics—is that all large worlds can be reduced to small worlds given enough time and computer power. We know this is not true (mathematically and otherwise). Some contexts simply cannot be compressed into the above conditions (filter, diagnosis, infrastructure, action) and therefore do not allow predictability in the above sense of assigning a probability. We can think, roughly speaking, of three sources of largeness. First, there is spatial or information incompressibility. In this case, we either don’t have the time and computational resources to solve a problem or it is in some sense absolutely unsolvable (for example, it would take longer than the remaining life of the universe, a not uncommon situation with certain classes of problems). Second, there is temporal or dynamic incompressibility. This form of largeness occurs when contexts change at a pace that prevents learning. Either the context does not have stable cues that allow us to learn or by the time we have developed a new model, or the world has moved on, rendering it mute. We could see this type of largeness as characteristic of the Anthropocene—it challenges the frequentist understanding of probability and its underlying vision of world stability that has reigned for most of the past century. Third, human learning and strategic behavior produce largeness. This form of unpredictability is where the problem of other minds from philosophy and the mathematics of game theory meet.

We are not helpless in large world contexts. Far from it. We can play. We can extemporize. We can explore them phenomenologically and ethnographically. We can send scouts and symbionts to explore in real time or develop capacities we lack (these are two of natural selection’s strategies for navigating largeness). These are all strategies that occur at the threshold or interface of small worlds and largeness. This interface is a crucial space for posing the problem of what it means to design institutions to bridge from the Anthropocene to the Holocene. We rarely, if ever, are only facing contexts characterized by smallness or largeness. Almost always, we are working at the interface of the two. Blindness to the role of one or the other (or hope that one will ultimately be reduced to the other) is an important epistemological error.

Put simply, small worlds are things we create and maintain. Predictability is the consequence of equilibrium, and like in physics equilibrium is the outcome of forces acting on an object from the outside. In wrestling with the problem of agency, we sometimes focus on the model (diagnosis and action) that the agent is working with, but often give insufficient attention to the context in which agents exist (infrastructure and the threshold of where smallness meets largeness). We exist in built contexts surrounded by architectural structures and institutions; our capacity to predict has to do with regularities created by these institutional contexts. But even though we can rely on models, algorithms, and predictions in small worlds, we cannot account for unpredictable large world events utilizing these same tools. Our entire cultural relationship to the problem of unpredictability will have to change.

Unbound Agents as Inter-World Beings

The relationship between agents and the worlds they inhabit is complex and multifaceted. In small worlds, model-bound agents have models of themselves within the world. These models are not just cognitive but are embedded in the built environment, in the institutional context, and in the social norms and practices that guide behavior. The models are part of what enables agents to make predictions and to navigate the small world effectively. However, the relationship between agents and worlds is not static. If you expand people's models of themselves, you can increase their scope and range of agency. If you control or limit their models, you can reduce their agency. As the legendary antiapartheid activist Steve Biko said, “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”1 This interplay between agents and worlds extends to large worlds as well. In large worlds, unpredictability and complexity challenge the agents' ability to make predictions. Yet, agents still learn to navigate these worlds, often relying on heuristics, intuition, and adaptive strategies. The relationship between the agent's model and the world becomes more fluid and dynamic. At the same time, failure is a constant feature of this navigation. In situations of true randomness, our predications can never be accurate more than fifty percent of the time.

This is where unbound agents become especially valuable. Unbound agents are not confined to specific models or institutional infrastructures. They can move more freely within and across institutional landscapes, and can translate these institutional dynamics in a way that makes them visible to act on. In many ways, unbound agents (who have often been marginalized through institutional violence and have found ways to survive within and again the reigning institutional semantics) have a far better understanding of institutional and “systems” than those running them. After all, their survival depends on being able to navigate complex institutional landscapes. It’s no wonder then that they possess profound insights into these landscapes. Unbound agents are often deeply embedded in communities at the periphery of institutional landscapes and from the limits of institutions—and in the spaces of their breakdown and failures—they traverse, critique, troubleshoot, and find ways to improve.

Largeness is a central problem of institutional design in the Anthropocene. By exploring the relationship between agents and both small and large worlds, we can deepen our understanding of how individuals, communities, and institutions interact, adapt, and evolve in various contexts, and design our institutions to better articulate the intricate web of connections that shape our ever-expanding world ecology.

- Biko, S. (2002). I Write What I Like: Selected Writings by Steve Biko. University of Chicago Press.

Figure 1. Decision Situation Map — Is this a small world or a large world situation?, author’s rendition.